Cathedral

A meditation on architecture, spiritual experience, collective memory, and time.

It was the local train. It made every stop. It was unromantic: all fluorescent lights and plastic panels and hard polyester seats. This was sometime during college. The train had turned out to be the cheapest way to get from Christmas with my mother and father in Geneva to a flight, departing the day after tomorrow from London, back across the Atlantic to Boston. I was in a window seat on the right-hand, northern side. It was midwinter, mid-afternoon, the sky already faded enough that the projected reflections of those fluorescent lights seemed to hover in the gray skies above the passing fields.

As my carriage pulled into the next of so many stations, big and small, fifty miles southwest of Paris, the view was unprepossessing—a spartan steel canopy over an empty platform, a prim little railway hotel with small lace-curtained windows and plastic flowers out front, a lonely parking lot. But the name on the sign was one to conjure with: Chartres. Oh, I thought, surely there isn’t more than one Chartres. But, I thought, you didn’t see any spires from far away. But, I thought, you weren’t looking.

Then the doors on the platform opened. The cool misty air found its way inside. The doors remained open. Spontaneity comes with difficulty, if you’ve had a certain kind of childhood. An inscrutable sequence of electronic bells sounded outside. My backpack was somehow still on my shoulders because, hours ago, I’d simply sat down with it on, too tired for the additional physical procedure of its removal, and just uncomfortable enough, mile after mile, for me to not do anything about it. I sat there, vaguely waiting for the doors to close again. You might never have another chance to see it, I thought. From scripture, I thought, we know not the hour. It’s been here for a thousand years, I thought, so it will be here for another thousand years. Even if you yourself won’t. You will have another chance, I thought. Probably that railway hotel has a room, I thought, probably it doesn’t. Get up, I thought. Go, I thought as I stayed in my seat, go.

The Cathédrale Notre Dame-de-Chartres is the cathedral of cathedrals. This is because it is the quintessentially cathedral-shaped cathedral—the stereotype and archetype of its kind. It has two narrow spires, as pointy as witches’ hats and some four hundred feet tall, above its front façade. It measures the same dimension—four hundred feet—in length. It has very tall walls, a hundred feet high, with very large stained glass windows, facing each other across a very narrow nave whose fifty-foot width was determined by the old Romanesque church on whose foundation it was raised. Notice the simplicity of these ratios: four to one, two to one, one to one.

The building’s longstanding purpose is to house a rectangle of white silk called the sancta camisa, believed by some Catholics to have been worn by the Virgin Mary as she gave birth to Jesus. A gift to Charlemagne from Byzantium, it had been found by a methodical empress who had traveled to the Land of Israel around the year 300 and collected artifacts willfully attested to by local oral history and vernacular archaeology. The camisa is called a secondary relic: not the primary holy body itself, but something that touched it, which, since the Virgin ascended undying to heaven, is as close as you get.

The Cathedral at Chartres also went up wondrously. By the standards of its time—and even of ours—it was built with astonishing speed: well within a generation, mostly between the years 1194 and 1225. This gives it, for all its vast scale, a rare coherence and a quality of instantaneity. It is visibly something undertaken swiftly, deftly, methodically, comprehensively. It is complete unto itself. It typifies what architectural historians call the High Gothic—the deeply articulated and corrugated formal style, all vertical ribs and spikes and niches and pinnacles, that is now doubly familiar in the developed West as the direct template for the Gothic Revival of the 19th Century. When you go for the first time, you will feel that you have been there before.

During that Gothic Revival, between around 1840 and 1860, the architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc was assigned with restoring and reconstructing Notre Dame de Paris. Though of greater ecclesiastical importance than Chartres, Notre Dame is an architecturally lesser building: it’s more visibly a shaggy bricolage from the different eras of the centuries-spanning period of its construction. Its squat and foursquare 200-foot towers never got their witches’ hats. In contrast, Chartres especially interested le-Duc because its rapid construction happened at the exact midpoint—and, by 19th century tastes, the stylistic apogee—of that very long time it took to build Notre Dame. So le-Duc used Chartres as a template. His post-Romantic approach was what we would today call pastiche or even kitsch: not to revert and reboot Notre Dame to resemble itself exactly as it was at any precise point in its past, but to make it as he felt it should be, as it ought to have been, and so as it could and should yet become. A stern distinction between the factual and fantastical did not especially need to be made. Those sulky chin-in-hand gargoyles on the postcards and that thrillingly attenuated spire at the intersection of transept and narthex were his inventions. In this way Notre Dame, as we have lately known it, is a modern building, manufactured with steam, iron and a self-conscious and willful anachronism in which High Gothic and Gothic Revival were, across their 600 intervening years, collapsed into each other.

You know about the fire. One of the things cathedrals do, when they’re not busy lasting forever, is burn down. The 2019 fire that burned down about a third of the physical structure of Notre Dame—recall the spectacle of le-Duc’s iron spire descending along its own vertical axis into a Miltonian maelstrom of flame—occasioned the last five years of rapid reconstruction. As with fact and fantasy for le-Duc, the distinction between the building and rebuilding of cathedrals, both so long in their undertaking, can be a matter of merely scholastic and pedantic distinction. But with the cathedral’s reopening this December, the fact of Notre Dame’s remaking is clear—maybe all too clear. A high-tech latex compound was applied to all the stone interior surfaces, which, when pulled from it like dried wood glue from a child’s hands, removed not only the char of the fire but all the previous centuries’ dirt and wax and wood smoke and incense. Everything is neat and tidy. “It feels like it was built yesterday,” said Adrien Willeme, a mason who worked on the rebuilding, to the Associated Press, “like it’s just been born.”

I don’t know how to feel about this. Resurrection is, to be sure, gratifyingly consistent with Catholicism. To attend Mass is to witness the same singular man constantly and simultaneously at the hours of his death and resurrection and on the day of his birth, across their intervening 33 years and three days—and also at the end of days—all collapsed into each other. In life we are in death. A 1936 book by modern Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier—about the promise of newness as found in the United States of America, and especially its skyscrapers—reminded its readers that antiquity was not an original quality of revered monuments, but one acquired over time. The book was released in America, right after World War Two, as When the Cathedrals were White. To see Notre Dame now—and again—in white makes it easier to console oneself that, along with a ruined planet, we shall bequeath to our descendants in the year 2725 at least a serviceable church in France. To be sure, from a practical and technical point of view, it would have been strange and complicated to restore Notre Dame not to some state of newness, not to a simulacrum of its high-resolution appearance in 1319, but to its moodier appearance in 2019. When you lose a third of your cathedral by fire into water into ashes, maybe submission to reason dictates that your only option for restoration is something that risks such uncanny novelty.

And yet. What, if not strange and complicated, should cathedrals be? What do we lose when we make old places new? Would it have been more interesting—more correct, even—to take the appearance of Notre Dame precisely back to 2019, even if that meant reproducing with Viollet-le-Duc-like artifice the visual effects of half a millennium of candle smoke? I know I would like to go back precisely to a point in time in 2019—to right before the pandemic that hit Paris so hard, a few weeks after that plague’s first European spark in Italy—and try to start again.

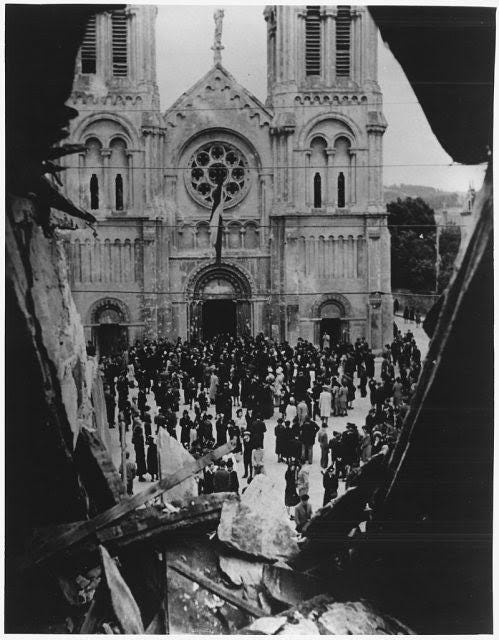

Notre Dame itself presented Parisians with a preview of such dilemmas, after an energetically-efficient cleansing of its exterior undertaken between 1991 and 1999—in anticipation of the millennium, an important year for Christians. That cleansing, like a too-close shave, turned the old and gray facade back to a peachy and uncanny yellow-pink. It no longer reproduced in real-life grisaille the famous black and white photographs of itself on Saturday August 26th, 1944, battered and bruised and sooty indeed, snipers on its parapets, at the famous Liberation Mass. The real had been detached from the apparent. Or was it the other way around? The famous front façade has since that scouring weathered with unanticipated speed—from peach toward champagne and ivory and even, in some lights, back into a birch-bark gray—which rapidity is asserted by some to be evidence of the damage, for all the illusions of restoration, done by removing the outermost layers from the stone. We can choose more mystically to believe that this is evidence of the insistent passage of the past into the present—ever more urgently with our attempts to repress it.

The same is unlikely to happen again to Notre Dame’s now-gleaming interior, in our age of cold diode glare and artisanal low-emissions beeswax. Now, at least in the images I’ve seen online, Notre Dame doesn’t much look like Notre Dame—as I still know and carry it inside myself from various visits: as an almost homely glimmer of glass and brass against a surprisingly intimate twilight of dark stone and workmanlike woodwork, against a jumble of susurrating crowds. Now, it looks more like the version of Notre Dame that you might see in such a video game as Assassin’s Creed, or as would be conjured by images excreted from the early simulated intelligence interfaces of late 2023 and early 2024, all oversaturated color and screen-like luminosity. Cheap mimesis. Tinselly beauty. Self-soothing stimulus. All digitally remastered for our mediated attention economy. The grimmest analysis would be that, however collectively unconsciously, we have rebuilt the real cathedral in that graven image.

Chartres Cathedral, which though it had long been doing just fine compared to Notre Dame, underwent in 2016 and 2017 an ostensible restoration that changed it unalterably and beyond all recognition. Walls the color of ebony became the color of ivory. A statue known for centuries as the Black Madonna came out white. Up went new-old detailing—gaudy or glorious, depending on your taste—in lapis lazuli and gold leaf. The main thing lost forever was the effect of the colored windows—their unique tincture called Chartres Blue—as startling galaxies of light and color against the eternal nocturnal abyssal darkness of the rest of the interior. By 2017, against the new bright walls, the windows faltered and became pale and watery, and even seemingly opaque, more eyelid than eye. Thus, strangely, the whole felt smaller and flatter: not a mysteriously unenclosed-feeling expanse attended by hovering galactic luminosities, but merely a high narrow bright box.

Many hated it. The restoration architect was quoted in the New York Times, with an utterly French combination of performative egalitarian piety and ancien-regime hauteur, saying, “I’m very democratic but the public is not competent to judge.” His idea had been to run it back to just how it would have appeared to our ancestors on the day it opened—presumably it was meant to present before those ancients an earthly paradise. The world made new. But our modern eyes will never be medieval eyes. We cannot now see even with 2016 eyes, with 2019 eyes, with this morning’s eyes. Or with the eyes of a world to come. Even if Chartres is now materially exactly as it was eight hundred years ago, it can never again to anyone now or ever living look as it once did. Precisely within the judgement of a public is where any place can be said most to exist. Maybe the truest cathedral, the one to restore and return to, is one that approximates most closely to a preponderance of collective memory shared by all the living and the dead who have passed through it across the centuries: the incarnation that would best be recognized by all those souls. This would be a building a little more beat up than the one that was presented on day one, its newness seen by only one generation. The very beginning of anything is rarely its state of perfection. To argue for an endless stabilization of the conditions of the first day would be to say—falsely—that any place is begotten only by its designers, and not also made, day by day, by those who dwell in it, over time, as it becomes itself.

A Cathedral in Time. That’s the turn of phrase famously coined in 1951 by the theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel, an actual professor of mysticism, to convey the spirit of the Jewish Sabbath: to relate how Jews—having been denied access by twenty centuries of Empires, from the Roman to the British, to the precise volume of space around which their land-based spiritual practice has since the Bronze Age been centered, the Temple and the Temple Mount; and denied in diaspora any other reliable contract to land and property—were able instead to find space in time. But not in mere endurance: “The sabbath is to time what the temple and tabernacle are to space. The sabbath is a cathedral in time. On the seventh day we experience in time what the tabernacle and temple represented as spaces which is eternal life, God in complete creation.” What makes this an observation of such compound glory is that a cathedral in space is of course also always already a cathedral in time: long in its becoming; long in its being, and yet its appearance always gradually or suddenly changing—with the cultural signification of its forms and signs in a constant state of resignification. There is no going back. When I was sitting in frantic lassitude in that train—electronic bells ringing, mechanical doors open—I was trying simultaneously to convince myself of the ephemeral and the eternal. To believe in the power of now and yet to have faith in forever. The river runs into the sea. The sea is never full. In the end both outcomes turned out to be true: Chartres is gone. Chartres is here. Chartres is preserved. Chartres is destroyed.

Yet, reader, it was so much better before. That’s why I’m glad that at the last minute I made it off the train, even as the sliding doors were closing behind me, bumping hard into my backpack. I walked up through the cold and unlovely town and into the cathedral. I saw it. I managed to steal at least this much out of time. In my memory, at that odd hour and in that unfashionable season, I was there alone. It was all I had dared hope and nothing I had ever expected. As an architect I’ve made some pilgrimages to sacred spaces—Hagia Sophia, architect Glenn Murcutt’s Australian Islamic Center in Melbourne, Le Corbusier’s chapel at Ronchamp, the Holy Sepulcher, Fenway Park—and like Viollet-le-Duc at Chartres, I’ve methodically mapped their designs and effects. But nothing has been like that was. Perhaps precisely because I was so unprepared that day for ecstasy, it was able to find me there. I don’t know how to tell you about it—other than that somehow when I imagine the sublime and inhuman mammalian joy of being a humpback whale suspended infinitely in a warm ocean, abyss above and abyss below, shafts of light evincing lysergically from the quicksilver of the waves seen from the other side—which I have been trying to do since at the age of three when I first heard a recording of whalesong—I conceive that it must be something like what being in that cathedral was like on that day, for me.

Maybe you, like me, were made in college to read Raymond Carver’s canonical 1981 short story Cathedral. The protagonist, inspired by a late night television documentary that they’re watching and hearing while smoking a late night joint, draws a picture of a cathedral for a not-especially-welcome house guest who is blind. The ballpoint pen inscribing palpably deep into a paper grocery bag, the unseeing man’s hands resting on and following the seeing man’s hands as he draws. The end of the story is that the protagonist draws the cathedral with his eyes closed, and that even when the blind guest invites him to reopen them and tell him what the drawing looks like, he keeps them closed. The final lines: “‘Well,’ he said, ‘Are you looking?’ My eyes were still closed. I was in my house. I knew that. But I didn’t feel like I was inside anything. ‘It’s really something,’ I said.” That’s what being inside Chartres that day was like. I was in my life. I knew that. But I didn’t feel like I was inside anything. I’m glad that, at least once, I got to know how that felt. I hope, but doubt, that I will get to feel it again.

It’s hard to know what faith is. For much of my life I have thought of it as a defensible legerdemain in service of organized religion’s useful worldly project of compelling ethical behavior. Around the time that Chartres was completed, the meaning of the word shifted over in English from mere fidelity—loyalty, trustworthiness, devotion—to this slightly other thing that is beyond belief: “neither the submission of reason,” to paraphrase the sturdy formulation of the 19th century polymath poet Mathew Arnold, who wrote this down around the same time Viollet-le-Duc was remaking Notre Dame, “nor acceptance of what reason cannot reach. [But] the being able to cleave to a power of goodness appealing to our real self, not to our apparent self.” More and more I think of faith as a specific experience of presence in absence, and so as a variety of something described by another word that the word rather resembles: grief. Perhaps especially of the harder forms of grief: of the anticipatory grief that continually prepares us for abandonment, by death or other means, by the one we love. A variety of the complicated grief that is immune to any sequential procession—a passion that cannot be mapped onto any orderly stations of the cross. Because I was too preemptively embarrassed to ask in my sub-schoolboy French, I never found out, at the town of Chartres, if there was room at that inn. I had spent all of the long dusk inside the cathedral and when I went back out into the world the sky was blue-black. Even enclosed by that blue-black I could also still see in all things the Chartres Blue. I spent most of that night sitting on the platform under yellow sodium lights, and just got on the next train when it finally came. That morning I arrived at Paris and killed time before the final train to London by going to Notre Dame and buying a wooden rosary that I put in my backpack and have since transferred to every bag that I’ve ever taken onto an airplane. My own sancta camisa, this artifact consistently stops the planes from falling out of the sky.

The only useful action in the world that my time inside Chartres Cathedral compelled in me—the only being able to cleave to the power of goodness appealing to the real and not the apparent—that I can attribute to that moment of space and time, came years later. It was during a brief and unprecedented road trip with my father. He was driving a rented car from London to Geneva in what turned out to be the last of the very many business trips that he loved, and the last time he was able to safely drive. He had for a long time been subject to the symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease, the immobilizing and grueling neurological condition that advances not gradually but in successive plummets and plateaus. We were just before the plummet that would lead to the last and lowest plateau. But we didn’t consciously know it yet. My presence in the passenger seat was his only concession then to frailty. He had a sense of dutifulness and orderliness that meant he liked carrying out a task once undertaken, without diversion. The caprice and chaos in my upbringing were—mostly—a matter of his absence. After we pulled back onto the highway from a roadside lunch—quintessential—of steak frites, I saw the spires of Amiens Cathedral swing up over the horizon. Amiens was, like Chartres just a hundred miles to the south and just a generation earlier, built at speed, between 1220 and 1270. It’s the largest cathedral in France. It looks uncannily like the child of gracile Chartres and robust Notre Dame, but grown so big that the latter would fit inside it twice over. It contains an object said to be the head of John the Baptist. I remembered Chartres. So I asked my dad if he’d ever been to Amiens. A devout Catholic and an architect himself, and so on lifelong pilgrimage to all ancient churches and all modern buildings of note, he had seemingly been everywhere. His legendary first date with my mother had been to see a cathedral in England, and for the rest of her life she made fun of him for having brought heavy Navy surplus binoculars with which to closely inspect the tectonics of the ceiling. You were supposed, she would say, to be looking at me. But to my surprise he hadn’t been to Amiens. To what turned out to be that one last church. Dad, I said, we could go, we could make a detour. But we need to get to Paris, he said. But dad, I said, nobody is waiting for us in Paris except us. That made him laugh—a victory. Suddenly I had given him the feeling that he could get away with something. Why not, he said, well why not. I’m easy. By the time we got to the cathedral it was about to close. We stood at a small wooden side door—one of those small doors inside a big door that you see in very big and very old buildings—still open. My dad with his charm which he never much directed at me, with his perfect French which I never much otherwise heard, with his guileless curiosity about strangers and his uncanny ability to draw grace from the habitually graceless, moved the formerly closed-faced gatekeeper to let us inside for a few minutes. The threshold of the door-within-a-door proved too high for him to step over. So I stepped inside on my own. But I didn’t let go of his hand, which I’d been holding to try to steady him across. He didn’t mind. Him standing three feet outside of the cathedral and me standing three feet inside it. Our arms fully extended, my left hand holding his right, above the threshold. Six feet apart. To my right I see across the transept to some luminous windows. To my left I see him framed and silhouetted in the pale outline of the doorway that was like a rectangle of white silk. Someone begins testing the organ. There were blasts of chromatic but unmusical sound that were terrifying and sad and funny. There was eternal life, God in complete creation. My dad died a few years later, a few years before the pandemic. He died old but also, after seeing my mother and the only person he had lived for die before him, he died hard. I am now none the wiser. I haven’t understood how to be without him. When I ask myself where he is, I answer myself that it’s just like this: I’m right here, with you and everyone else living, just inside the cathedral, and he’s right there, just outside the cathedral. It’s really something.

What a beautiful piece of writing. I'm crying small secret tears in my office cubicle this morning.

Magnificent. I will be pondering this for a long time. Hopefully while imagining myself standing within a cathedral, an old, unrestored cathedral.