We have moved on. Ours is the era of looking.

We visited galleries and heard lectures, watched arts programming and read criticism, all that time like we were wandering a highway gas station in search of a piece of fruit. Is any substance to be found here . . . substance . . . any, at all? We listened to looped conversations, open-ended, never-ending. “What does this artwork say about us?” “Well, it raises questions.” “Questions about what?” “About how we think of ourselves.” “And how do we?” “We think of ourselves very dourly and often.”

The talking never stopped. Their highest praise for an artwork was that it prompted conversation, gave them reason to talk. Things they discussed were worldly, social and theoretical. Some critics lamented how the commercialization of art had ruined their enterprise—but were not critical conversations being had, out there, beyond the pages of periodicals, continuous, overlapping, the activists’ hot litanies, clinical patter of the seminar, all sorely needed, urgent and ongoing, in ever-widening, more open, more welcoming spaces?

Had the intrinsic value of great art been self-evident to them, those who ran museums might have said the institutions existed for the art in their collections. Instead, they said museums existed to inspire conversation and the exchange of ideas. Art was for audiences to explore the issues that concerned them.

We are free of such concerns. All that talk is noise to us. We’re here and here to look.

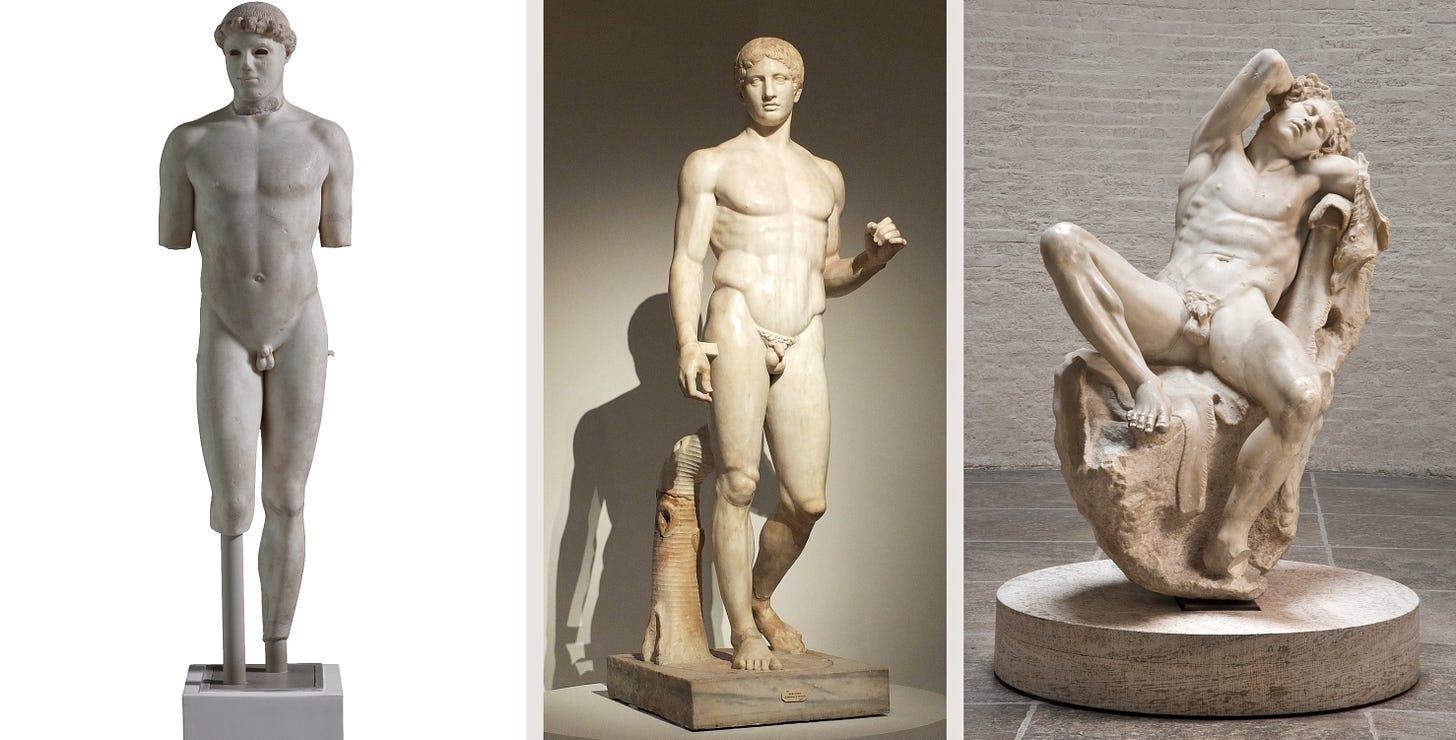

The artists who first used their eyes show us how to see. Our subject is that which claimed their full visual attention. Representations of the human form are there in our prehistoric art through to the figurative art of the great early civilizations—but it was the Greeks of the 5th century BC who perceived as we never had before, whose sight awakened, and what they saw was the human body.

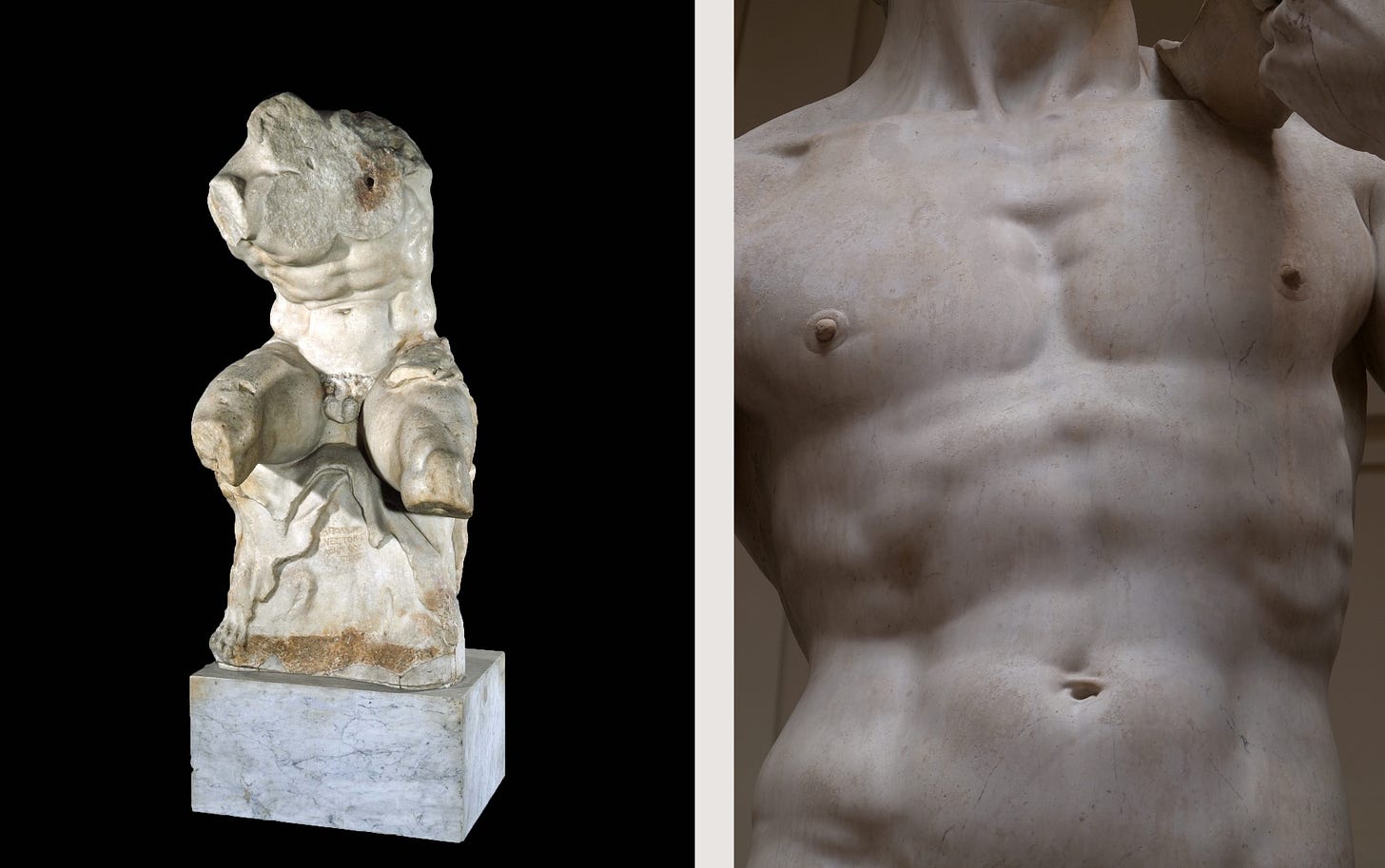

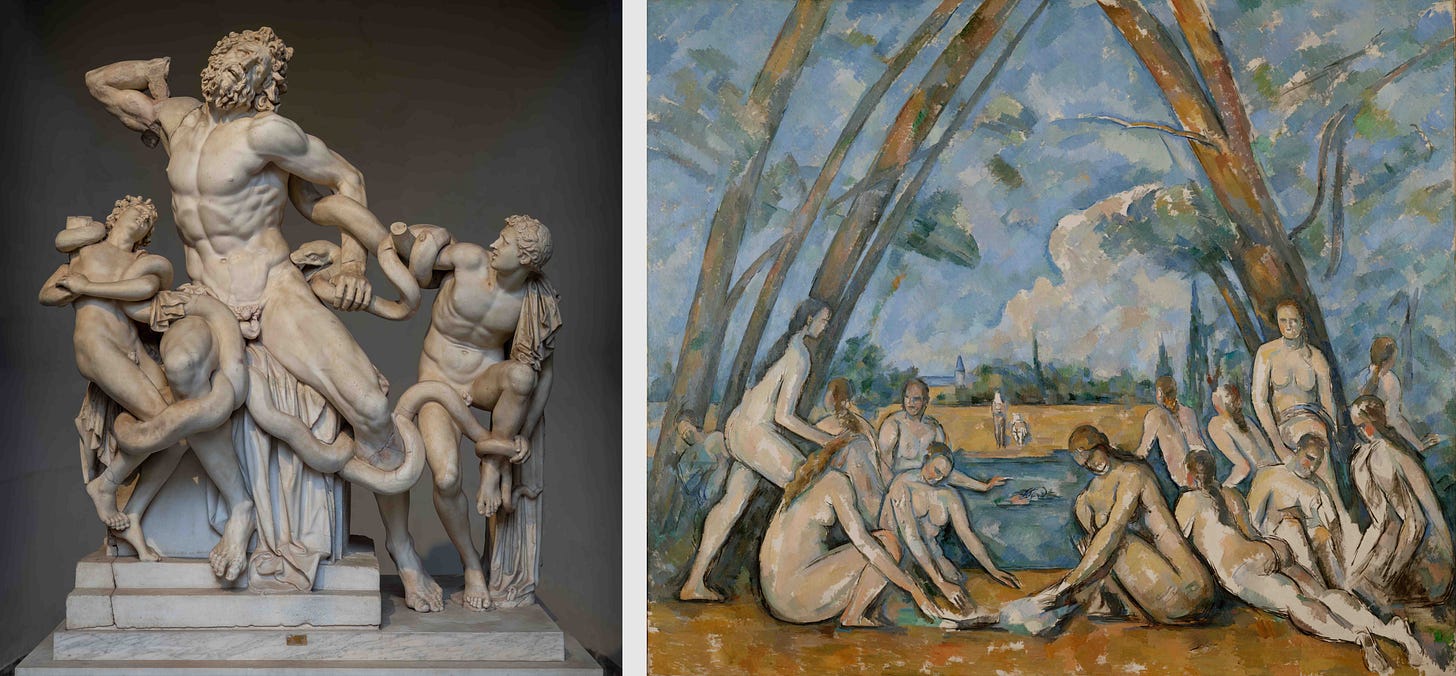

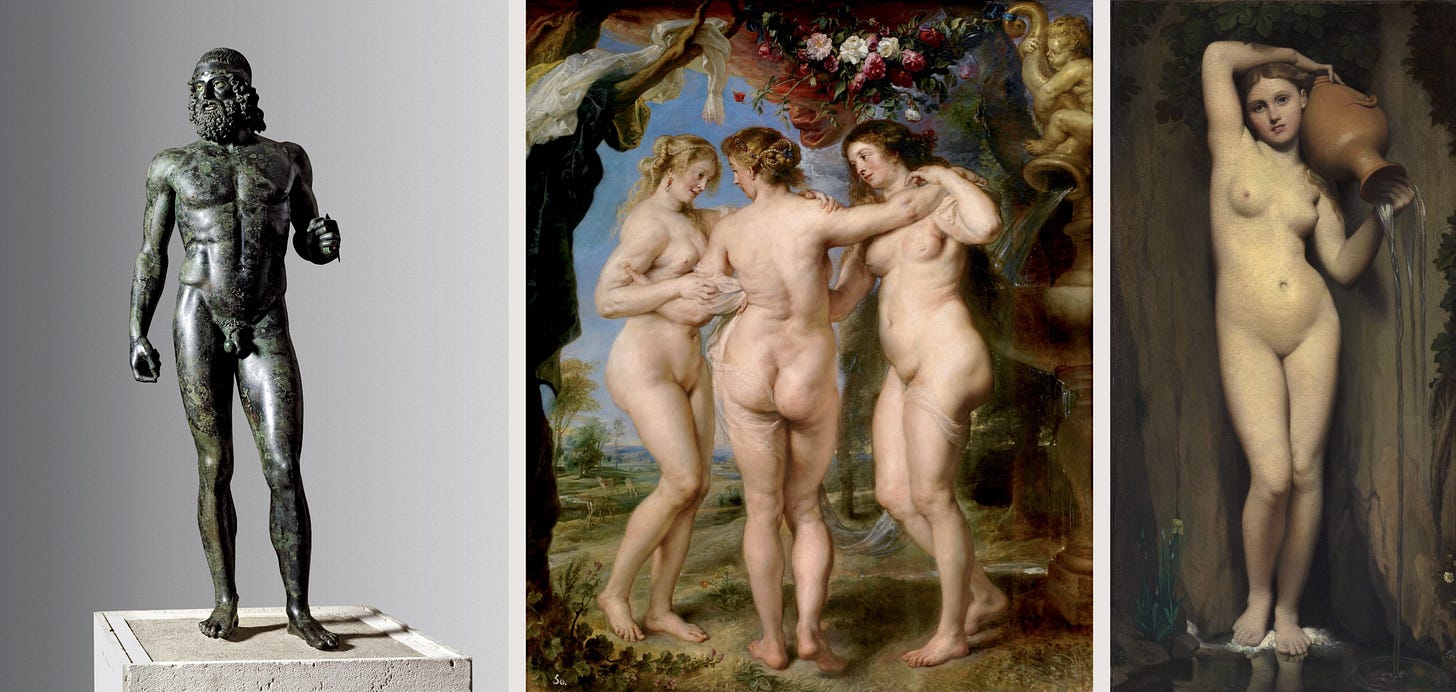

Figuration can train the eye as abstraction cannot: This much is obvious. For the artist, so for the viewer. And what object could be more worthy of depiction than the unclothed human figure? In the span of a few decades, with the Persian Wars going on about them, the sculptors and painters of early Classical Greece revolutionized the style of their art such that they revolutionized its substance. What so angered Plato—the new illusionism—was the breath of life into marble, bronze, and pigment. With the birth of naturalism, the features of Archaic art (the stiff arms and clenched hands, the flat feet, rigid hips, and passive smile) left the body; and in came anatomical accuracy and far more: movement, animated asymmetry, character and emotion, narrative surrounding the figure, shoulders that engage, torsos that might glisten, hips that rock and sway, and skin as we know our own, to the touch.

Their nudes were soldiers and victorious athletes and heroes, those favored by the gods and so raised to them in dedication—and their nudes were gods, Zeus and Apollo, Dionysus and Hermes, and a little later, Aphrodite and the Graces.

To love divinity, to love vigor and abundance, harmony and one’s ancestry, was to love the body.

From few original works and many Roman copies, we can follow a thousand threads: how the human figure, once given life, became real and swiftly more than real; why the names Phidias and Polykleitos are with us after two and a half millennia; the spread of Greek naturalism across the Mediterranean, into the Near East, and down through antiquity; changes in artistic craft; how, like the Baroque spun out from the Renaissance, nudes of the Hellenistic period after the Classical became increasingly theatrical and emotive, tipping into the extravagant.

The forms, or motifs, these artists captured are such embodiments of unalloyed human states and qualities, are so spring-loaded with resonance, they ricocheted through the centuries—assimilated, adapted, echoed, and alluded to by later artists. Our eyes can trace all this.

After antiquity, reverence for the body returned again in the 1400s in Italy. Borne of the new will to know physical reality, to perceive the world around them and trust their sight, Brunelleschi invented linear perspective and the Renaissance painters and sculptors following him rediscovered the nude. We’re spoilt for nudes from that time on.

In public and private life today, a person’s primary visual encounters with imagery of the naked or semi-naked human figure are through neither art nor worship but advertising, entertainment, and porn. It’s pathetic that this is true. We choose another way.

That men once stood before the Rokeby Venus and gawped means nothing to us.

In the bleak mid-January of 1972, British households with their television tuned to BBC Two were invited by the critic John Berger to join him in “question[ing] the assumptions” of the Western art tradition. Berger’s audience was the general public, and the analysis he offered not only was taken up, quite immediately, as the dominant intellectual approach to the nude but remained so in the decades that followed.

Ways of Seeing defined the nude as a naked person made into an object and thereby stripped of their humanity. For Berger and generations of feminist critics and artists, the nude in Western art history is exclusively female, is passive, and so embodies stereotypes of femininity that both reflect and reinforce the status of women (as object, as vulnerable, as sexually available) in Western societies. That Berger was oblivious to the ancient tradition of the nude form is plain. Moreover, he psychologized the nude figure—saying “the truth about oneself” is denied her—to the point of wild conspiracy.

We were raised in a culture where the conspiracy theory of the male gaze received near total institutional endorsement. Nakedness in art existed, according to our educations, for the purpose of “male consumption.” Art was said to be a service industry like any other, with male artists serving their male patrons’ libidinous needs.

Feminist scholarship emerged as a political project and an expression of the concerns, often intensely personal, of a class of professional women living in the seventies. Art was a wall they could tack their social hang-ups onto. Half a century has now passed. Their hang-ups are not ours.

To us, they are like those evolutionary psychologists who explain romantic love as “a biological lease agreement.”

When art historians called the nude “a tool of colonialism and conquest,” “a means of naturalizing power differentials,” we have ignored them, as we do any other raving lunacy. They cared about the treatment, visual and otherwise, of women’s bodies in the history of Western society. We care about paintings.

What knowledge of art did their analysis ever demand? If they spoke of the Venus de Milo, it was to deem her “typical.” The names Felski, Kristeva, Kant, and Derrida filled their indexes. No Praxiteles or the Pergamene school, no Giorgione or even Correggio.

They saw in artworks only what they had already decided was there. You would never know from how the social or feminist art historian described a nude by Ingres, among them some of the most arresting depictions of the female form ever created, that it isn’t a digital illustration but a painting, oil on canvas. For them it was an image, one expressing social norms.

With these approaches, inevitably many scholars gave up on the pretense that artworks needed to be looked at, at all. So they became historians of art history itself, their own discipline; they spoke not of images but of discourses and texts—and a new conspiracy arose. The genealogy of figurative art as a record of influence and innovation stretching over centuries, the passage of motifs through history, directly and in memories and traces, is a phenomenon as real as the moon in the sky. Any time given to those who think the canon, this material record, a discourse is time wasted.

The nude in art gives pleasure. Since the art of Ancient Greece, pleasure has been inherent to the subject. The existence of nude masterpieces that seem to us pure manifestations of aching lament, of nudes that are distressing or alarming, only confirms this. We want the nude to take us where awe and serenity meet, or else lure us in and invigorate, for the reason that its gratifications have no equivalent in other spheres of life. Nothing approximates beholding the Belvedere Torso or Michelangelo’s David.

Directing at the nude our whole aesthetic attention, seeing it as we do, is more pleasurable still. Sophistication is pleasure.

Those who deem the nude in art a “sex object” betray themselves as prudish and crass. Certainly history has seen its share of plastic-seeming nudes. The most candidly erotic paintings of 19th-century French academicism are largely artifacts of the past, and those artists barely remembered. Their marks on canvas captured something synthetic, not life; their works have more in common with modern advertising imagery than with the finest nudes in art.

Every nude is an occasion for the eternal drama between realism and idealism to play out. From the art historian Kenneth Clark, we can discern three senses, at least, in which a nude may be “ideal”: as in beautiful, as in unreal, as in expressing an idea or concept. The last meaning is most significant to Clark’s study of the form. For him, the foremost nude figures in art are substantiations of the archetypal forces and states that distinguish our species—ecstasy, pathos, energy, Apollonian clarity and order, divine and physical love. Much of our sight we owe to him.

Clark did falter in underestimating, or downplaying, the sexiness of the great nude tradition. Few passed-out, drunken men are as hot as the Barberini Faun. The Doryphoros of Polykleitos, for all his mathematical perfection, is more than beautiful. His body looks Adonis-like to us: Aphrodite herself might steal him from his mortal lover.

Feminists suppose that a thin line separates high art from pornography. From our vantage point, the line is prominent. “Everything is oversexualized, nothing is sexy” has been a valid complaint about our culture for a generation. Only the most immature mind conflates sensual attraction and prurience. It is no coincidence that the naturalistic nude form was invented by a people who believed in physical life as spiritual life. That which appeals to our animal nature can be a thing of reverence.

Five decades after airing Ways of Seeing, BBC Two brought to the screens of British living rooms The Shock of the Nude by classicist Mary Beard. What had changed? With her village-pantomime delivery, Beard presented a history of the Western tradition in which artists, patrons, and audiences are a mass of “blokes” and behave accordingly. There are memes with more penetrating cultural analysis than was offered here. Beard selected controversy as the theme around which to organize her hodgepodge of nudes.

As an animating factor in art, and as a subject in itself, controversy is over. To overstate its staleness is impossible. A swirl of talk, and then an empty subject for further, ever-more-desiccated post-controversy talk: This is all it can be.

Public controversies surrounding artworks including nudes have been generated and sustained always by idiots. When it was erected to the façade of the Palais Garnier opera house, Carpeaux’s exuberant sculpture La Danse caused a scandal. Klimt was almost run out of Vienna for his “perverted” Faculty Paintings. Because he depicted them with pubic hair, Modigliani’s nudes were taken away by the police when first exhibited. More recently, Hylas and the Nymphs by Waterhouse, a scene of proto-anime banality, was removed from Manchester Art Gallery by hapless interventionists, and a show of Titian’s poesie paintings sent critics into a moral flap about the artist’s imagined pardoning of sexual violence.

Except where they succeed in destroying or irreparably altering works of art—as in the case of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, which had much of its nudity painted over the year after this death—why should we care about the life-squandering outrages of idiots?

The intensity of loving art necessitates aloofness to public controversy. We adore Manet. We know its historical context such that we feel the proper shock of Olympia; and we know the era of Manet is over.

Our educations aside, proof of the male gaze conspiracy’s acceptance is found in the state of the contemporary nude. “Find something here to gawk at!” appears to be the sentiment driving many of them. Newer nudes fall into two main categories: those that are said to celebrate the variety of the human form, and those that are expressions of anxiety. Each type stems from a reaction to the Western tradition, well or poorly understood.

Because we are not anxious about our bodies or pleasure, most contemporary nudes confound and bore us. Lucian Freud’s repetitive oils from the seventies onward, Louise Bourgeois’s nude sculptures and watercolors from her later decades, all self-portraits of anxiety in disguise, confound and bore. Sharing Dürer’s aversion to the body, both artists made nudes for the neurotics of the world.

Marc Quinn’s and Jenny Saville’s nudes are the epitome of artwork as mere conversation starter, the subject for classroom assignments. Who wants to look at them for long? No line connects these artists’ confrontations to Manet’s.

Ugliness is in no way disqualifying. Intensely expressive, unsightly nudes go back to the Hellenistic period. Dark visions and fanatical curiosity drove master painters as unalike as Goya and Schiele, and in our own time Marlene Dumas, to create their sublimely ugly nudes.

In an age saturated with images, the faculties of perception are coarsened and weakened, like silk put through the dryer. Refining and strengthening one’s sight, a rewarding enterprise whenever, is only more rewarding now.

We are greedy and honest. To the extent that being historically informed helps us see, we’re all for history’s contexts. When our eyes tell us otherwise, we trust our sight. The raw facts convey that Savonarola, he who set the bonfires of vanities ablaze, mounted Donatello’s David in the courtyard of Florence’s city hall—implying he found no eroticism in the sculpture. But we know what we see.

Of course we’d become citizens of ancient Knidos for a day and visit Praxiteles’s Aphrodite at her sanctuary, if we could. Who doubts that a gulf separates the ancients’ world from ours? Lamenting this is like lamenting that we haven’t wings. Even Roman spectators were unable to experience Classical art for its original religious force. For an artwork to mean differently over time is not a tragedy.

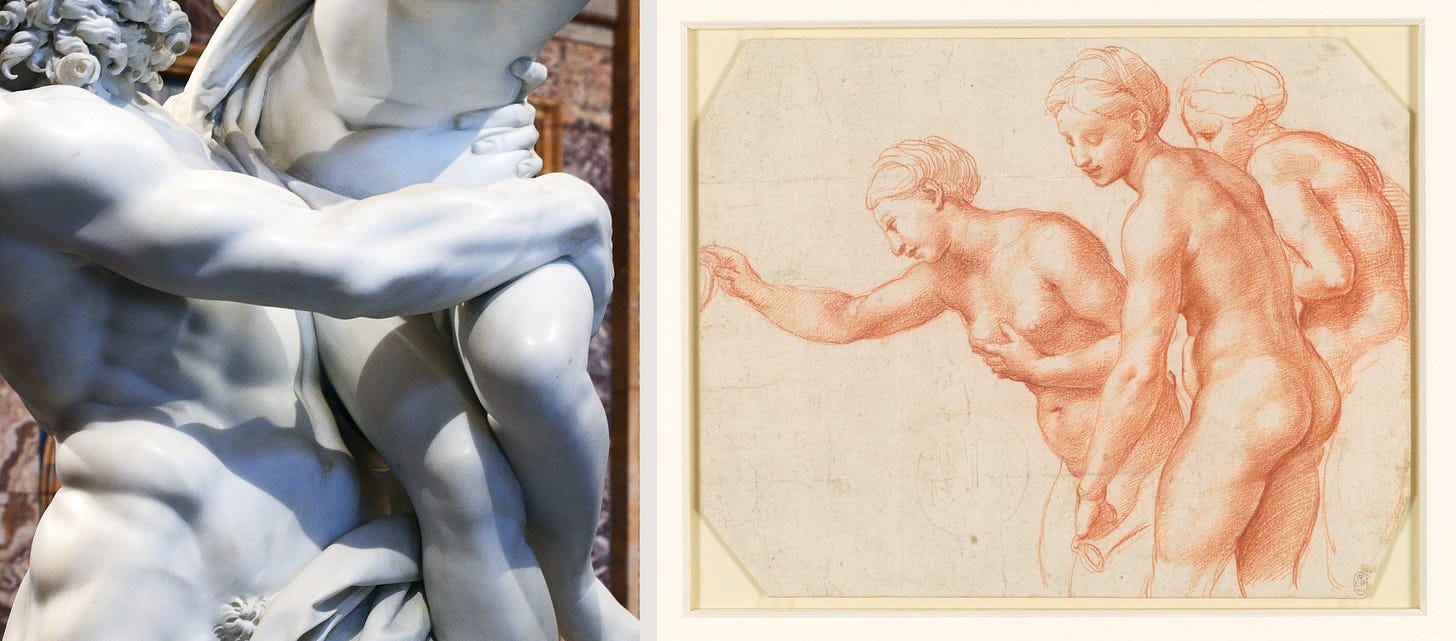

Our focus on perception is as far from watery subjectivity as it gets. Robust formal knowledge is what allows us to see. Take the unrivaled naturalisms of Myron and Bernini, how they differ. With the Borghese nudes, the Baroque artist gifts us human bodies of such gorgeous and shocking realism, emotions real as our own, marble soft as flesh, we forget all storytelling and we witness. The Athenian, living two millennia earlier, with his Discobolus captured a moment of such unspoiled potential, all torsion and intent, it’s a wonder the sculpture never inspired a poem by Keats. Myron’s idealist nude, whose muscles do not strain as a real discus thrower’s would, is a portrait of human honor and self-command, the stuff civilizations are made of.

Paint is what paintings are made of, and attentiveness to an artwork’s materiality is most of the work of looking. There’s no separating an artist’s treatment of a figure from their treatment of paint. For a century and a half, France alone gave us experts on the nude—Corot, Courbet, Renoir, Degas, Bonnard, Matisse—who used light and color and brushstrokes to the most divergent effects.

For all that we use the term naturalism, history’s great artists never claimed to represent the body in its natural state. The artistic drive is borne of the instinct, too strong to be articulated, that nature’s provisions are inadequate, they do not satisfy. Birdsong is not music enough. We believe in artists themselves as the great believers. Made things can communicate what would otherwise go unknown, unfelt, unexpressed: Every great artwork is a manifestation of this instinct, this certainty. Art is not a bundle of questions but the hard record of an answer. A nude study by Raphael, with its simple clean outlines, its red-chalk shading as soft as caresses, is a manifest certainty.

In the middle of 1508, having heard of the young painter’s accomplishments in the north, at Perugia and Florence, Pope Julius II summoned Raphael to Rome. The artist was then twenty-five and would take on as his first solo commission the decoration of a state room in the Vatican’s new papal apartments. That room, the Stanza della Segnatura, served both as the meeting place for the papal court’s high tribunal and as the pope’s personal library. Over three years, Raphael painted its walls and ceiling in fitting with the Stanza’s private function.

The School of Athens fresco, covering one wall, is known to us from innumerable book covers and website banners, and for its portrayals of Plato and Aristotle, Pythagoras and Heraclitus, and Raphael himself. The painting represents philosophy (including science) as one of the four major realms into which man’s wisdom could be divided—that is, the four principal subjects of Pope Julius’s book collection. Theology, jurisprudence, and poetry are each represented on the other three walls. In the Parnassus fresco, the god Apollo, playing music, is surrounded by the nine Muses along with poets from the present and past, including Dante, Sappho, and Homer.

Even here, at the seat of the Catholic Church, the spheres of philosophy, law, and the arts are not subordinated to religion but treated as complementary, distinct. In our own time, the subordination of art to discourse, the endless talk of sociologists and theorists, is no longer abided. We give our attention to the art.

Alice Gribbin's essay makes art feel like something I can simply meet—no pretense, no academic scaffolding, just my lived experience, my senses, my eyes. She reminds me that engagement itself is enough, that I don't need permission or authority to have a relationship with what I see. Her argument feels both revelatory and inevitable, as if she's articulating something so fundamentally true that it's been waiting just beneath the surface of our conversations about art. Art isn't a puzzle to be solved or a text to be decoded, but a living experience to be encountered with full attention and open perception.

This essay inspires and reassures in equal measure. In 2017, I abandoned an MA in photography at a highly-regarded college. Everything, I was told, was power swaddled in discourse. My male gaze, and every other datum of myself, was ipso facto suspect. No amount of sackcloth and ashes would be sufficient. I didn't pick up a camera again until last summer. For the previous years, taking pictures had been re-upsetting, a shutter release for unhappy memories.