Dear Nadar, I must beg you to renounce these terrible balloon-antics

-George Sand, 1865

1.

Winston Churchill said the entire history of the British Navy could be summarized in three words: Rum, sodomy, and the lash. In Richard Holmes’ Falling Upwards: An Unconventional History of Ballooning (2013), Holmes presents a similarly fraught history of the first century of ballooning: a history of madness, recklessness, and death. One in which balloons, a technology Holmes describes as both “extremely modern and extremely primitive,” are the preoccupation of criminals, priests, and explorers—the realm of the radical who wants to leave earth and go up.

There is evidence that as early as the 4th century, the Chinese were using balloons to signal to armies on battlefields. There is also oral evidence of shamanic practices involving balloon flights taken by priests in pre-Inca civilizations. Peruvian funeral rites often involved sending corpses floating high over the Pacific. Yet until the 19th century, ballooning was strongly linked with fantasy and dreams. Many of the early balloonists were former prisoners, who’d spent years imagining an ascent to freedom inside their debtor’s prison cell, before finally making it a reality. During the early aeronaut craze, Napoleon fantasized about an invasion of England involving an entire French army attached to balloons. Holmes says Benjamin Franklin caught the balloon bug in France as well, and imagined a solitary walker being able to leap over miles with a simple hydrogen balloon attached to their back. Franklin once said, “Someone asked me—what’s the use of a balloon? I replied—What’s the use of a newborn baby?’”

Holmes is at his best in Falling Upwards, focusing on the three narratives that seem to interest him the most: Sophie Blanchard, Charles Green, and Solomon Andree’s Polar Expedition of 1896-7. Sophie Blanchard was an early French pioneer, who, in 1810, once “flew so high and the temperature dropped so low, that she suffered a nosebleed and icicles formed on her hands and face.” She typifies the era's ignorance concerning things like atmospheric pressure, weather patterns, etc. Once, in order to avoid being trapped by a summer hailstorm, “she climbed so high . . . that she lost consciousness and spent 14 ½ hours in the air as a result.” If there is a common theme to ballooning in the 18th and early 19th centuries, it’s losing consciousness, or discovering that you are now many miles away from your intended target. Holmes shows that for a period of decades balloonists lacked even a basic understanding of how to land their balloons. Broken backs, paralysis, broken arms, and fractured skulls were the norm. Crashing into houses, crashing into chimneys, crashing into bushes, crashing into trees. And if you survived…wanting to do it again.

Holmes believes flight fascinates us because it follows a dramatic three-act structure: Ascent, flight, and descent. Sophie Blanchard, who symbolized sex appeal and danger to French audiences of the period, met her final descent on July 6, 1819. She ascended over the Tivoli Garden in Paris, and from there was supposed to “discharge some fireworks that were attached to her car.” For a moment, Blanchard disappeared behind some clouds, and when she reappeared spectators observed flames, and then a pause. She fell through the air to her death, tangled in what was left of her balloon, down onto the rooftop of a house in the Rue de Provence. Then her body fell again, into the street, “…and Miss Blanchard was taken up a shattered corpse.”

All true ballooning stories end like this: with an aeronaut’s spectacular death.

2.

Of course, it wasn’t long before these early radicals were replaced by an often-repeated phase of human and scientific development: Commerce. In the 1830s, Charles Green, the British balloonist, negotiated a contract with the Vauxhall Pleasure gardens to host balloon events as part of the garden’s attractions to Londoners. In the preceding years, Green had made several innovations, such as replacing hydrogen with coal gas—which made balloon travel cheaper—and developing a guide rope to hang below the balloon, giving aeronauts the ability to stabilize their elevation in flights below 500 feet. The Vauxhall balloon was launched in November of 1836 in order to drum up publicity and set a sought-after long-distance land record. The balloon had a large basket and was equipped with supplies for its three-man crew: lobster, 40 pounds of ham, sixteen pints each of sherry, port, and brandy, and several dozen bottles of champagne. On the ground an adoring audience looked up, uP UP, for the first time as Green and his crew rose over the London crowd, which included a young writer named Charles Dickens. Passing over the English channel into total darkness and on to the French night, Green decided to play a trick as they passed over a shift of poor factory workers below.

Green “lit a blazing white Bengal light, and lowered it on the rope until it was skimming ‘nearly over their heads.’ He then urged Mason (a fellow crew member) to shout down through the speaking trumpet ‘alternately in French and German,’ as if some supernatural power was visiting them on high.”

The terrified iron workers below, unable to see the balloon above them on the moonless night, were unsure if they were being visited by some god of the sky. The crew continued on through the darkness, almost dying after a rapid and violent descent due to changing air pressure (and losing their expensive coffee press) before crash landing in Germany. Yet the most disorienting experience for the crew was the sensation of total darkness in pre-industrial Europe. A darkness so black that it felt like a solid object, and they were being sucked inside of it. Their experience of the blackness, Holmes states, was like the “shivering anticipation of the Victorian horror of being buried alive.”

Upon crash-landing, Green and his men were shocked to discover they had traveled 480 miles in less than 18 hours. Green soon gained an international reputation for this voyage, and ultimately—respectability. A kind of death for any artist or aeronaut.

3.

Holmes ends his volume with one of the finest set pieces in all of his work. A passage and story so haunting in its scope, it “becomes a much larger symbol: the end of the romantic era of ballooning.” By the end of the 19th century, Sweden believed it was falling behind Norway in its race to the North Pole. In 1897, Swedish balloon hero Soloman Andree proposed a unique solution that was in many ways still seen as a novelty: balloons. Andree would launch his balloon and pass over the geographic North Pole before landing in Russia (thus, capturing the record). He had designed a new balloon and developed a new trail rope to help navigate (trail ropes are now ridiculed by modern balloonists). His three-man crew consisted of himself, Knut Fraenkel, and Nils Strindberg (whose father was the cousin of the famous playwright). Nils Strindberg’s family and mentors begged the young man not to go on the expedition. The 25-year-old Strindberg had recently become engaged to his childhood sweetheart, Anna. However, Anna loved him so deeply she wished for her soon-to-be-husband to pursue his scientific dreams. She knew that when he returned, they could settle down and start a family.

In July of 1897, Andree’s three-man crew shook hands with their well-wishers on Dane’s Island and ascended. Within moments, the trail ropes failed, and the balloon began to drag across the icy water. Andree had failed to test the balloon upon its arrival from the manufacturer, and it may have been leaking hydrogen as well. From this point on, the primary information we have about the expedition comes primarily from Strindberg’s “extended love letter to Anna, nine pages written in shorthand, which he intended to deliver on his return as a wedding present.” Strindberg would also present perhaps a more important document: The photographs he took along the way.

For two days the men struggled through the frozen fog and low elevation, dealing with the strange atmospheric pressure of the frozen north. In many ways it appears that they believed they were at the beginning of a new chapter in ballooning history, not realizing that they were writing its end. Eventually, Andree’s balloon crashed into the ice pack. The men were unhurt. During this tragedy, Strindberg reacted as perhaps we would today. He thought, “I need to take a picture of this.”

This is perhaps the saddest photograph in all of ballooning.

Holmes writes, “The rest of their story belongs . . . not to the air, but to the ice.” The men’s spirits appeared to be high. Strindberg is almost jubilant in his unsent letter to Anna. The men began the next day to hike south, needing to cover 250 miles in 110 days before the arctic winter set in. They shot a polar bear and fed themselves. However, they soon discovered a hard truth. The North Pole is not a land mass. It is a shifting sheet of ice. After several days marching south, “their sextant bearings showed that they had actually moved north.” No matter how quickly they tried to move south, the ice was moving north, trapping them.

Strindberg wrote of these days in his unsent letter to Anna, “’The weather is pretty bad; wet snow and fog; but we are in good humour. We have kept up a pleasant conversation the whole day. Andree has spoken of his life…’” With the saved material from their balloon, the men heroically fashioned a balloon-gondola to cross over the icy water, but they were forced to land on White Island, still 200 hundred miles away from their nearest supply dump. By October, the men knew they wouldn’t make it.

Strindberg stopped taking photographs.

The last entries of his journal read:

6th October: Snow storm. Reconnoitering

7th October: Moving.

17th October: Home 7 o’clock a.m.

It remains a mystery what occurred between October 7th and October 17th, but Holmes points out the strange use of the word “home” in Strindberg’s final entry. A Swedish search party was launched in both 1898 and 1900, but nothing was found of the failed expedition.

It wasn’t until 1930 that a whaling ships’ shore party discovered what was left of the lost expedition. The doomed men “had deliberately wrapped up and set aside [their] journals, diaries, and letters.” They also discovered Strindberg’s sealed photographic tins. Holmes states, “Through all their hardships he had never abandoned them.” The whaling party soon pieced together the evidence. The corpses of Fraenkel and Andree were found first. Both bodies had been destroyed by polar bears, post-mortem. By the placement of the expedition’s objects it was discerned that Andree had died last. They finally discovered a nearby fissure in the earth covered with large rocks. Inside, they found the body of the third crew member: Nils Strindberg. Holmes states that the grave, “had been lovingly and laboriously constructed, at what must have been a terrible cost to the dwindling physical reserves of his two surviving comrades.” The two men may have perhaps died from exhaustion by constructing it.

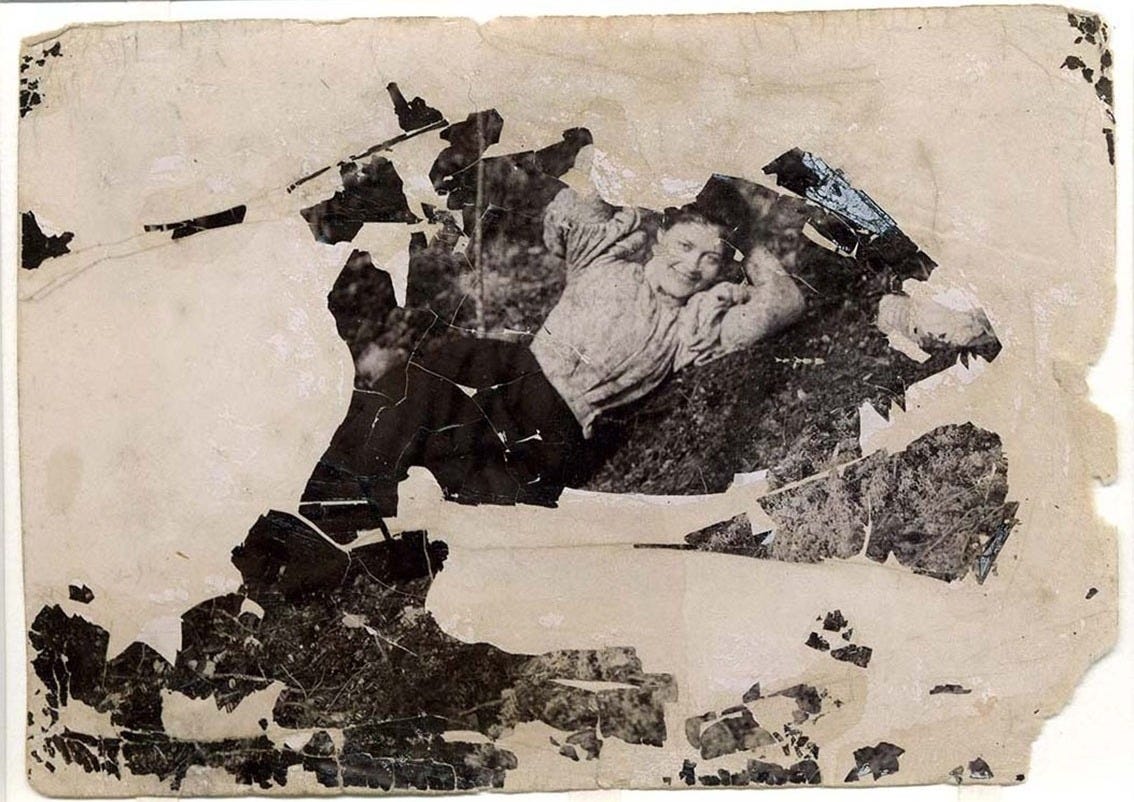

After the death of her fiancé in 1897, Anna had married and moved to America. In 1930, she was almost an old woman now. Yet she had left instructions upon her death, that her heart should be removed from her body and buried with Strindberg, if his remains were ever found. When Strindberg’s personal items were returned to her there was an engagement ring, and his extended letter. There were also his photographs and the snow damaged image of a smiling woman from the 1890s.

It was perhaps the last thing Strindberg had seen upon the earth as he froze to death.

On the back of the photograph was a single name: Anna.

The axis of heroic world history seems pretty well drawn and delimited. The godlike spirit and the unrelenting vigour are well recognized in their familiar geo-cultural domains.

Swiftly added to my TBR pile