Last year, at a Panera-catered “new faculty appreciation” luncheon, the Dean of my college told me—as I folded my hands across my seven-months-pregnant belly—that I should look for long-term academic employment elsewhere. My research and practice was not centered enough on “AI” and “emerging technology” to fit within the institution; they wanted someone with more of an explicit emphasis on tech. My work in publishing, writing, web-design—and even my reproductive state—couldn’t possibly be separated from these things, but, more than any other effects AI may have on humanity in the future, this is one of the main effects now: people feel compelled to talk about it, and it’s a good way for sclerotic institutions to feel like they’re keeping up with the times. I smiled, thanked him, and left with an M&M cookie.

Earlier this month, at the recommendation of a colleague, I registered to attend a Zoom seminar that boasted a discussion on “the future of design education and academia.” As the Zoom window expanded, I was met with a looping Pornhub threesome montage next to a side-screen grid of six or so designers front-facing the camera. The hosts clicked around, grunting and gasping as the camera cut to new angles and positions. I opened my department group chat and texted my colleagues OH NO. DO NOT JOIN THE CALL. The colleague who recommended the talk echoed me: DO NOT LOG IN! SOMEONE Hacked their Zoom.

The hosts spoke to each other saying things like:

I think it’s you.

Wait. Oh wait. No.

This type of thing happened all the time during Covid. So annoying.

Who is *bot-generated-username*?

It was a long two minutes before someone finally had the sense to end the call.

A few hours later, a nearby university, who employs one of the guest speakers, posted a carousel of screenshots on their Instagram page from the talk, which had apparently reconvened. The description read Thanks to our Program Director ************** for an amazing panel discussion on the future of design education & academia today! 🚀

I tried to follow up with the panel about what happened, and received no reply.

The way this talk was handled reminded me that technology, for all its promise of connection and innovation, can have real and tangible repercussions if we’re not careful—it illuminates our fundamental responsibility to one another.

In “A Rant about Technology,” Ursula K. Le Guin says that technology is how a society copes with physical reality. That it is the active human interface with the material world. Technology is also a spoon. Technology is also language. Yet, I am shocked when AI does not stop Outlook Messenger from bursting confetti across my desktop in response to the Congratulations reply I receive when HR misreads my email about both adding and removing our late son from my health insurance.

As a 6th grader in a Dallas suburb, I attended a school assembly where a traveling speaker talked to us about sex. He said that sex was like fire. It was a life force. The discovery of fire sparked a massive advance of civilization. He told us that if we were not careful with fire, if we did not watch it closely and respect the power that it held, we could burn down a whole village. He told us to start a fire someday, but only with someone who you trusted to tend to it while you slept. I believe now that this same sort of diligence must also be extended to our use of technology.

This year I experienced many technological interventions to my body, as many do when they become pregnant. Of all the new ways to be measured and monitored, my favorite was when my sister-in-law, due just a few weeks before me, guessed my midsection's exact circumference with a piece of string. My least favorite was the transvaginal ultrasound. My OB in Virginia had a sort of nonchalance and slapstick humor to him that initially made me feel comfortable in his office. The temperature changed during my nine week appointment when he, quite unexpectedly, shook the ultrasound wand inside of me (with vigor!) in an attempt to wake the baby for the pictures. He mutter-yelled Move little bugger. Move! I looked to the nurse witness, who looked forward at the door. We received a letter in December that his practice would be closing in April. We received another at the end of summer telling us that he had died.

During this same pregnancy, another doctor does imaging on me, externally. With the wand in his hand in the almost pitch black room he tells us that there are two small and one moderate-sized holes in our son’s heart and that he will need to be rushed to surgery as soon as he is born. I am still fully reclined and covered in gel. He tells us to come back in two weeks. On his walk out of the room he hands us an information pamphlet where he drew on the back two versions of the human heart—one normal, one our situation.

Because of this experience, we transfer care to Massachusetts, where my husband’s family lives and works in the medical field. We navigate this with someone who is known as “The worldwide head of second opinion.” At the new hospital the gel is cleared off my belly each time. I cry in the ultrasound room as the video of the baby in my belly is labeled “practice breathing.” The sonographer walks us to a conference room where we’re met with cardiac specialists, social workers and obstetrics. Our meetings are prefaced with This is going to be a hard conversation and when we stand up to leave the room, we are encouraged to take the entire box of tissues with us. Someone even goes to the cupboard to get us a new box, of superior quality and softness.

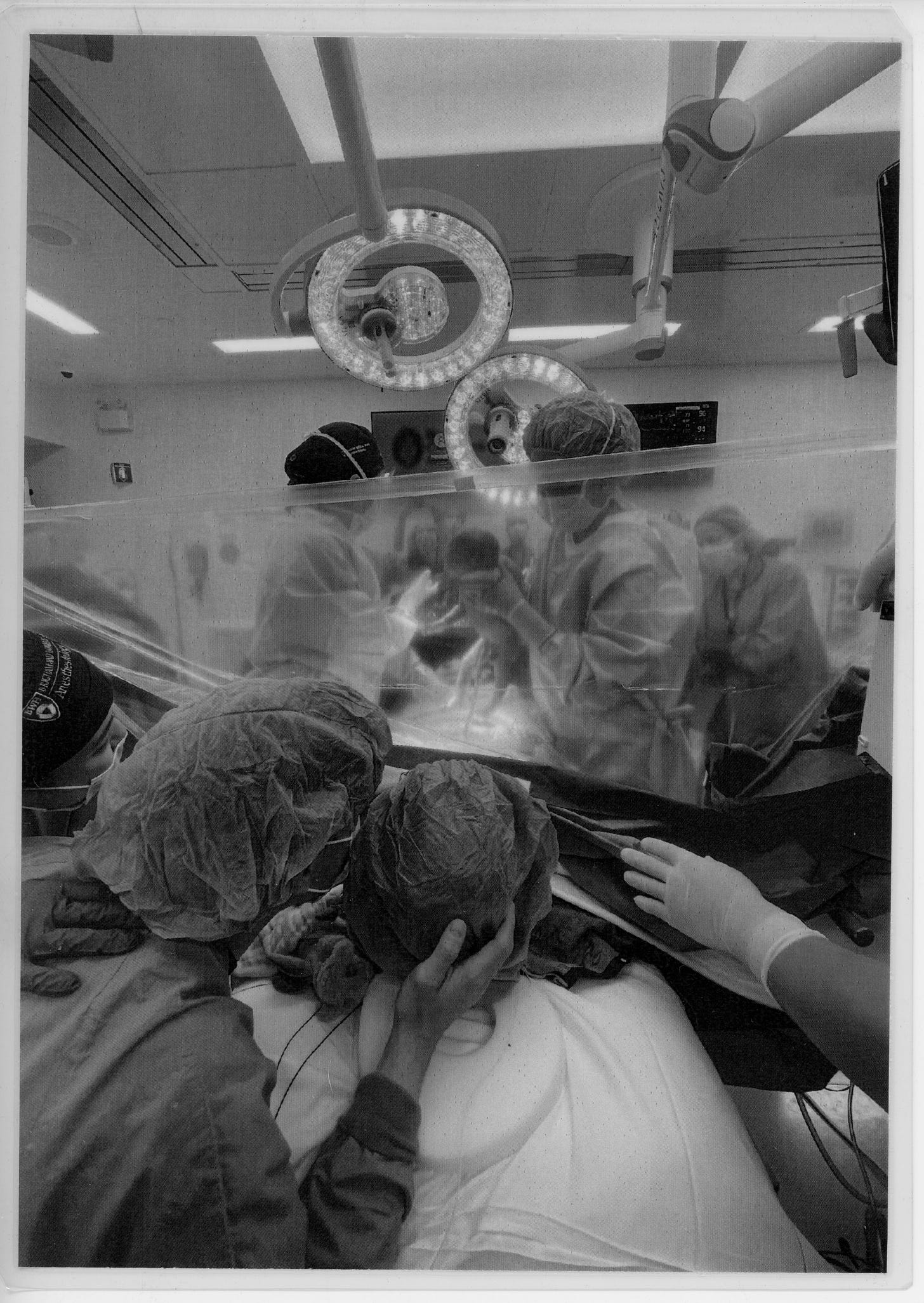

We are told that we may not get to meet him, but we do. The windowless OR looks perfectly encapsulated in pure even daylight. We have a team of thirty people and everyone knows the choreography. The anesthesiologist tells me that I may feel a shock of sorts before she administers a liquid into my spine. I am beaming. I feel strong and I wait for the shock. I squeal. The staff echos my laughter when I tell them that it feels like I sat on a firecracker. They had not heard that one before. The team yells out Happy Birthday Henry! as he is lifted from my abdominal cavity, screaming and alive. The anesthesiologist tells us with urgency to touch him and she guides our hands to meet his head through the dividing screen. I keep my fingers at the place he fogged the plastic as he is carried away to receive care.

While my layers are being stitched up, my husband notices that the TVs near the ceiling are screening the surgery from above. When a nurse sees him watching, they switch off the monitors. The birth was photographed by our social worker, who printed and laminated the images. A whole stack is waiting for us in our room on the meal tray when we return.

When I see him next, there is a whole room dedicated to beating his heart. I am wheeled to his side and told not to worry about the beeping, it is just an indication of a new switch to flip. That it is not as time sensitive as it sounds. Henry wraps his hand around my finger, then around the beak of his woodpecker Jellycat. He is on a high platform and adorned in wires and tubing like some sort of cybernetic king. One part of the room-machine spins constantly. It whirls and re-oxygenates the donor blood that has exited him in a slightly less vibrant shade of red than what entered.

He fights for two days. On his third, when he chooses peace, it is the quietest room I have ever endured. The cardiologist encloses us with the curtain and lets us stay as long as we can.

We have a mass in Henry’s name. Afterward, family comes over. They bring food and two new pink babies. I hold my niece and keep checking that my hair does not wrap around her fingers. Our dog screams in the face of the two-year-old cousin, who seems completely unaffected. He says “dog” and pats him. He points to the angel on the mantle and says “Amen.” We set up a small box in the living room with photographs printed out from the hospital. As his mother, I feel protective of his image. I do not want people to look at him on their phones. I want to be in control of how he is seen in his corporeal form. I want people to sit on the couch and hold him, looking together at the same time and passing him around as they would any other baby. I become upset when I log in to Facebook for the first time in years, to sell a lamp, and see that some of our pictures from the hospital were posted to the family’s facebook group. I stew on this for a while, then release it when my husband reminds me about when they were posted, his first good day on the ECMO machine. We were two proud normal parents. They were asking the family for prayers.

During the next three months, I look at his pictures for fifteen minutes every three hours to trigger a milk letdown. I imagine kissing his head and can still taste his baptismal holy water on my lips. Smell the perfumed oil. I nurse a small machine all summer and a refrigerated car comes by to pick up the milk that will be processed, divided, and sent off to babies I will never know. My husband wakes up in the middle of the night to wash the flanges, label the bags, and place them in the freezer. At home, we keep a white noise machine of the ocean waves playing in the bedroom at all times. We have done this for years, but I only just now am paying attention to it. When my dog unplugs it, I notice its absence.

Earlier this spring my department chair threw me a baby shower. My students ate cupcakes and giggled as we failed to answer baby related pop-culture trivia from the 80’s. At the end of summer I send them a sad email to thank them for their patience last year and I ask for it again. This fall I sit in class with them, smiling as laughter bubbles from the corners of their mouths in response to the recording I play of Richard Brautigan reciting this poem:

I like to think (and the sooner the better!) of a cybernetic meadow where mammals and computers live together in mutually programming harmony like pure water touching clear sky. I like to think (right now, please!) of a cybernetic forest filled with pines and electronics where deer stroll peacefully past computers as if they were flowers with spinning blossoms. I like to think (it has to be!) of a cybernetic ecology where we are free of our labors and joined back to nature, returned to our mammal brothers and sisters, and all watched over by machines of loving grace.

I took part in another Zoom call this week. Henry’s cord blood was collected for research and after five months, the results came back. They were able to find the exact single gene mutation that caused his condition, and explained everything. They assured us that it was not our well water, or the time I had a fever for 15 minutes, or leptospirosis from cat-sitting, or that I ate an underdone yolk. The doctors said that with the variation he had, they were surprised that he was able to make it to two days old. My friend Mary texted me a message her late father used to say about heaven.

We are there before we’re born and God asks us if we want to come down to Earth even though it will be painful and hard. Seems Henry wanted badly to be yours and to meet you if only for a single shining day.

Neither my husband nor I carry this gene. And the doctors tell us that the same thing is unlikely to repeat. They clear us to try again this year.

Lately, my husband and I have been watching a lot of TV together. Football when we’re grading so we don’t have to see the Patriots lose. And movies at night. There is a scene in the film Magnolia by Paul Thomas Anderson where frogs begin falling from the sky. They drop to the pavement violently, cars crash, and there is a little boy sitting in a library at a desk looking out the window cracking a half smile in wonder. Shadows of amphibious bodies cast on the wall behind him as he says out loud This happens. This is something that happens.

This is profoundly moving. Thank you for writing it, and for choosing to publish it. It is helpful - and beautiful.

Raegan I am sorry for your loss of your beloved son. Your article touched me and made me want to cry for you. I lost a daughter at five days. It has been forty years since she died. Your article brought the feelings back up in me. I really liked how you wrote about the experience in such a matter of fact real world way. Thank you for sharing this. May God bless your family.