At a party earlier this summer an editor maneuvered me into falsely claiming I’d read a book I hadn’t read. Most of the time, when someone asks you if you’ve read something you haven’t, you can just nod and they’ll go on. It’s a form of politeness. They’re talking, this book has occurred to them, it’s important to the flow of their thought, and so they just automatically ask if you’ve read it and you nod politely and they go on. If people were scrupulously honest about which books they’d read, conversations at literary gatherings would become impossible.

But the editor didn’t go on.

“And how would you describe that book?” he asked.

The small crowd around us looked at me expectantly.

“Describe it?” I was stalling for time. I was trying to remember the front cover.

The editor gazed at me through his glasses with fine, clear eyes.

“Yes,” he said. “I’m just trying to find the words. You must know what I mean, it’s just so…”

He stopped. Everyone was staring at me. I felt a prickle of sweat along my scalp.

“It’s kind of hard to talk about,” I stammered.

“Try,” he said. “Please.”

“Yes,” said a woman from behind me. “Try.”

There are people behind me, I thought in a panic. I fought the urge to turn around.

“It’s a very good…” I said, praying that he’d finish my sentence.

He looked at me kindly, mercilessly.

“A very good?”

At this point I could sense, in my peripheral vision, people’s expressions beginning to change. End this, I told myself. End this now.

“It’s a good way of thinking about death,” I blurted out.

My answer seemed to disappoint everyone. The conversation deflated, and slowly, the crowd dispersed. Upon my return home, I vowed to read the book, which had been sitting on my shelf for years. I discovered it was excellent, a small masterpiece of critical writing. But it was also deformed by a basic mistake.

TJ Clark, in his book The Sight of Death, assumes that he knows about death. Clark assumes that death is the end. This assumption isn’t his private error: It is not hyperbole to say that this assumption is the most basic requirement for entry into the high culture of our time. Our culture believes that life is a length of brightly colored material, under which—nothing.

In asking me about this book, the editor might have been wondering if I had something to say against this assumption, something that might expose the mistake on which the edifice of contemporary high culture is built. People with a sense of the achievements of the past are more or less constantly asking themselves why our own culture seems doomed to triviality; why nearly every work of visual art produced over the past forty years, hanging in one of our prestigious museums, is utterly trivial. Moving from the 17th century galleries to the contemporary galleries is like falling into a pit of nothingness. Ascending the staircase from the past to the present is like descending into hell.

In the book, Clark writes about Poussin’s “Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake,” in which a man is running, his eyes angled down and to the left, looking at a man killed by a snake. The running man, seeing death, looks dead. After finishing Clark’s book, I went to look at the Poussins that hang in the Cleveland Museum of Art, next door to my office. The CMA has three Poussins. Two of them are relatively early paintings which have experienced significant decay. The third is in good condition, and was created in the 1640’s, the apex of the artist’s career—“The Holy Family on the Steps.”

As soon as I saw it, I realized that if TJ Clark had written his book about this painting, instead of the painting about the man killed by the snake, what I’d said to the editor at the party would have been correct. “It’s a good way of thinking about death.” Because the picture isn’t about death. It tells us that death isn’t particularly important or even interesting. The painting is an image of undeath.

How do I, not having died, know this? Because the painting taught me.

The closer I studied it, the more I realized what the painting was teaching me. It cast its colors and shapes like fishing lines into me, pulling out the materials with which it would perform its lesson.

*

When I was young I was afraid that life would end. Now, I am disturbed by its unendingness, and in particular at the way it doesn’t end. Half-asleep in bed at 11pm, three or four weeks pass through my mind—it’s summer—four weeks of summer days— pink and grey skies, leaves moving in the wind, heat—and for a moment, the finger of my right hand, trailing off the bed, index finger extended—my finger pushes through the vaporous surfaces of those days and I touch the hard unyielding stone surface of time itself.

You can do this when time starts to move fast enough. My father told me time starts speeding up when you turn thirty. I’m 48. When you’re young, you’re focused on the things, the people, the scenes. When you’re young that’s all there is. But that isn’t all there is. And when time goes fast enough you can actually reach down and touch it.

It’s shocking. The feel of it. Smooth unbroken neutral cold substance.

Don’t take this on faith. If you are over thirty, observe yourself how fast the days go. You can get a whole month in your mind at once. You couldn’t do this when you were twenty, could you? A whole month at once. Can you get 28 or 30 separate things in your mind at once? No. But these 28 days are not 28 separate things. They are one thing.

What is it like, the color of those days evaporating over the raw stuff of time itself?

Smoke rising from stone. A cloud of colored smoke over stone.

It’s tempting to flee from this perspective, this insight, perhaps the sole certain insight granted by age. Tempting to flee back into the color, back to the living bodies. But stay with it for a moment longer.

Sometimes, contemplating the sheer speed of time, it is as if I were looking at a pillar. I’m very small, the pillar is very tall.

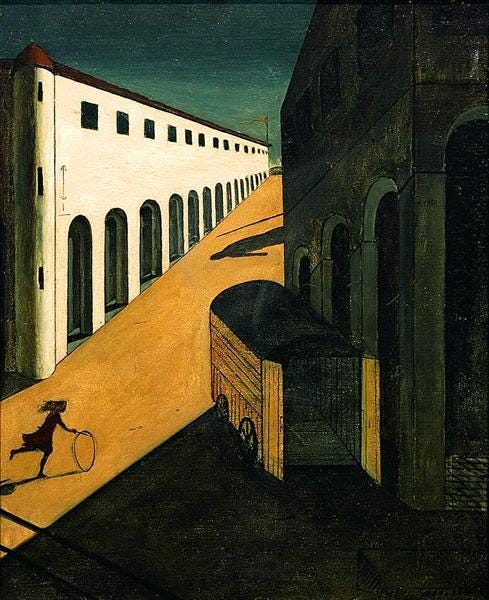

If I were a painter, and were to paint this feeling, it would look like one of Giorgio De Chirico’s surrealist paintings from the 20th century—a fragment, a stutter of architecture in a space filled with smoky color, over a ground that records the disappearance of human shapes.

In De Chirico’s paintings we see the long shadows of unseen personages cast under lone arches. Broken aqueducts. Single pillars. These forms correspond to the insight I received on my bed, trailing my index finger through the stream of days and touching—with a shock—the cold shaped stone substance of time itself.

But in Poussin’s painting, the architecture does not stutter. It coheres. And the personages aren’t shadows. They’re complete, shining in bright light. The architecture forms the background supporting a central group of figures—the Holy Family. This group of figures itself takes an architectural shape—the oldest shape known to the west—a pyramid.

Poussin has borrowed the pyramidal shape Renaissance masters gave to their holy figures, but nothing in Leonardo or Raphael prepares you for this pyramid. It is wider, flatter, sharper. In Raphael, a group of colored bodies resembles a pyramid. The group of people at first just look like a group of people. It is as if Raphael shows us the process by which the mind discerns geometrical order behind the visible world. He displays a deductive process. And it is best to think of his pyramids in terms of geometry, as neutral mathematical shapes.

But Poussin’s pyramid is a building. No one could look at “The Holy Family on the Steps” and see a group of people. We see a pyramid made out of bodies. This is not an order underneath the textures of ordinary experience, but above them. Made of them.

A pile of boards does not have a house behind it. The house has the boards behind it. The painting doesn’t show us what’s behind our world. It shows us what our world is for, it shows us the things that our world, our lives, are behind. Super realism.

What Poussin shows us is not something any individual could imagine. De Chirico and I, working only with our solitary selves, can reach down through the rush of ephemeral ordinary experience and touch bits of the unknown architecture of time.

What Poussin shows us is that time is a coherent structure. Time is a building on which a pyramidal human family rises.

The painting also has something to teach us about nature. Three natural entities survive the transition between the world of ordinary human existence and the realm of undeath. The first and most important is the sky.

When I look out my window as I write this, I see a lawn, a forest of trees, all in bloom here in the middle of summer. And above that I see the sky, light blue, with a few white clouds.

When I lie in my bed half-asleep, and weeks of past time rush by me, I see the slow evaporation of the colored smoke that the trees and lawn are made out of, and of human bodies, but I do not see the color of the sky. The sky is a different kind of thing, and its color—a light blue—occurs relatively rarely in nature, and then mostly in things related to the sky, like birds or certain eyes.

Emily Dickinson uses the color blue to signal the approach of a state beyond death. As when she describes the buzzing of the fly she hears when she passes out of life.

“Blue uncertain stumbling buzz.”

The blue sky in “The Holy Family on the Steps” could very well be the sky I am looking at from my office window right now.

As part of the process of learning undeath from the painting, I take a photograph of the sky as it appears from my office window. I then print it on a color printer and cut out a small length. I print out a reproduction of the “Holy Family on the Steps” and I paste the photograph of the sky from my office over the rectangle of sky in the painting.

The painting doesn’t change.

Then I try pasting small cut-outs from photographs of Greek and Roman architecture over similarly-shaped pieces of architecture from the painting. This ruins it. Pasting pictures of my face and the faces of people I know or famous people over the faces of the Holy Figures is even worse. It gives the painting a distinctly demonic look.

What does this teach me? That the sky is a part of nature that is in some basic sense out of nature. At the end of my book Gamelife, written long before I encountered “The Holy Family on the Steps,” I wrote this sentence: “When I die, I will remember the color of the sky.” This is a fragment, a stutter. But Poussin’s painting confirms its essential accuracy, while placing it in its correct position in the complete and coherent order of undeath.

Now I ask: How does the sky relate to the architecture? Look at the steps. They lead directly to the sky. The sky is part of this super-real architecture; the ideal building integrates the real sky.

So Plato was wrong. We do not live in a false and illusory world, underneath which is an enduring world. Our world is a kind of mosaic, composed of pieces of transience and pieces of eternity. This fact is what makes art possible. Poussin can give us certainty about undeath by activating the genuine experiences of undeath that stutter through our life.

Another piece of nature is the fountain, or, more precisely, a stone basin from which a few drops are falling onto the stone pavement. It is a lesson about time. It is not a lesson that can be rendered verbally. It must be experienced through attention to the absolute silence and stillness of the architecture, the figures, the sky, and the plants. Attend to this silence and stillness. And then notice how, at the far corner of the space, a few drops of water are falling.

The drops when they fall sound on the stone pavement. Can I understand how sound renders silence perfect? How a movement creates motionlessness? How still-falling drops make a stillness? I can.

*

The painting begins its last lesson through the form of the family. I did not understand how the form of the family reveals a different shape of time until I became a father. That is, until my family extended both before and after me.

Mary and the infant Jesus form the apex of the pyramid. The light is strongest here.

Prior to becoming a father, I existed all at once. Like a single drop spilling over the rim of the urn in the painting. My existence was characterized by a sort of looseness, an untetheredness, a singularity. What did it feel like? Like falling.

After becoming a father, part of me, maybe most of me, isn’t here, isn’t in me. I am something that a photograph can’t capture. I extend in both temporal directions. I extend in bodily shapes that bear only attenuated similarities to the form of me that can be captured by a photo.

When I was in New York at the party—where I was manipulated by the editor’s kindness and respect for my wisdom into lying about reading the TJ Clark book—I did a Zoom call with my wife and daughter. And when the image of my family flashed into being on the screen before me, it was like a circuit being closed. As if one of my limbs, having fallen asleep, suddenly woke into tingling life. Looking at my daughter’s beaming face, at the excitement of her eyes, traveling over the background, probing the depths of my hotel room—I didn’t feel happy, exactly. The feelings that mattered weren’t in me, weren’t in my body. They were in hers.

I enjoyed the resumption of my being across three hundred miles of space, through the days and hours of my physical absence, when her thoughts and movements had traced out esoteric designs on playgrounds, in preschool classrooms. When the screen went dark at the end of the call I didn’t feel lonely. What the bathroom mirror showed as I brushed my teeth was just a point on an arc—other points glimmered in the past, in other parts of the present, in the future.

Thinking of the way I inhabited time before becoming a father, and instructed by “The Holy Family on the Steps,” I am struck by the watery quality of this prior existence.

I floated in the air. I had no intrinsic connections. And this, I think, was why I was so afraid of death, why I overemphasized its significance. Death is the kind of thing that can make a significant difference to one who floats—isolated, moment-by-moment—in the air.

And I am thinking now—the painting is making me think now—of the decision to have a child. It is a decision that can only be made by faith. From the far side of the decision, the transformation of the very nature of time, the altering of one’s being, is not really imaginable. It can’t be taken into account. The philosopher L.A. Paul calls this kind of thing a “transformative experience.” It presents a challenge to our culture’s submission of life to free individual choice.

Before becoming a parent, you can take into account the sleeplessness, the boredom, the expense, the restrictions that parenthood involves. But you can’t take account of the reorientation of the self in time, the way these disturbances will come to seem, not as a warping of one’s entire being, but as drops of water falling, in the corner of a space, deepening an essential stillness.

I think the painting now is teaching me a lesson about faith, a lesson that can only be learned from the perspective of certainty.

*

I start typing an email to the editor who, with sublime unconscious esoteric Machiavellian kindness and manipulation, got me to read the TJ Clark book. When I start typing the email I fully intend to tell him how I’d lied about reading the book, about how my lie had been a gate through which grace entered, about how I’d read the book for the first time, and what it had led me to.

This, after twenty minutes of typing and deleting, is what I finally sent:

Dear Lorin, Just a brief note of thanks for leading back to TJ Clark's Sight of Death which I haven't looked at in many years. It truly is an unreal masterpiece! Best, Michael

I am conscious of having failed. I re-read the email with humility. I promise myself that I will write about this, write the truth, and then send this into the world, and send it to him.

*

Now at last I am looking at Mary’s eyes. Her eyes are dark. Poussin has captured something essential about vision. I think this might be the only truly accurate and certain representation of vision in a painting. Her eyes are not positive, they are not objects.

Mary’s eyes are open doors or gates or hollows, and the angle of her vision shows what they open to, what they receive. The perfection of her face reveals something of the condition of reception.

But look at the angle of her vision.

Mary is not looking at the steps. She’s not looking at Jesus, or at John the Baptist. She isn’t looking at us. She isn’t looking up either, which would be a symbol--a symbol of transcendence or of heaven. Her gaze exits the picture plane.

I am looking around my office now. I am looking at my daughter. With my eyes half-closed, on the meditation cushion, I feel for the angle at which vision comes loose from the world, from this moment.

When I am half-asleep and time speeds up faster and now whole years and even decades pass under my trailing finger, I am turning my neck slightly in the half-dream. I am pushing my finger down at an angle.

I’m always looking for it now.

I turn my thoughts into words and push them down, at an angle, through you who read this, through days and years and decades.

Searching for what I am now certain is there.

Enjoyed this, nice work, Michael!

This was really interesting and thought provoking. I think the first painting..man killed by a snake , brought you to the Holy Family painting. The first painting is also illuminating. Age also brings you to realizing that after you die, others will continue on as ever. the boy running up will be surprised at the quick lossof life, but he will go onwith his day..maybe telling others his news..That is about all that will happen there…But, I believe the dead man with go on to a great adventure. That is obvious by the surrounding beauties of nature and as you say theskies. Thank you. PS. Im a grandmother. Wait till you area grandfather, id love to read your i nsights then!

, brought